Once the majority of Latin American was free from Spanish control, freshly liberated countries began developing their unique personalities. Sometime near 1850, many started pondering and debating how to cohesively name what we now know to be “Latin America.” Nearly all major countries south of the United States gained Independence in the same interval, but Brazil’s uniqueness as having been under Portuguese control left folks at odds, considering the huge cultural difference between Spanish-influenced nations and Brazil. For the most part, Brazil wasn’t ever grouped in with ‘Hispanoamerica’ (the appreciated term for Spanish America, as it avoids links to Europe). Opinions between the two were largely contentious; Brazil’s association with The United States isolated them from their neighbors, Brazil’s history closely resembled the U.S., a relation that obliged Brazil to nearly endorse the United States’ exploitations in Hispanoamerica.

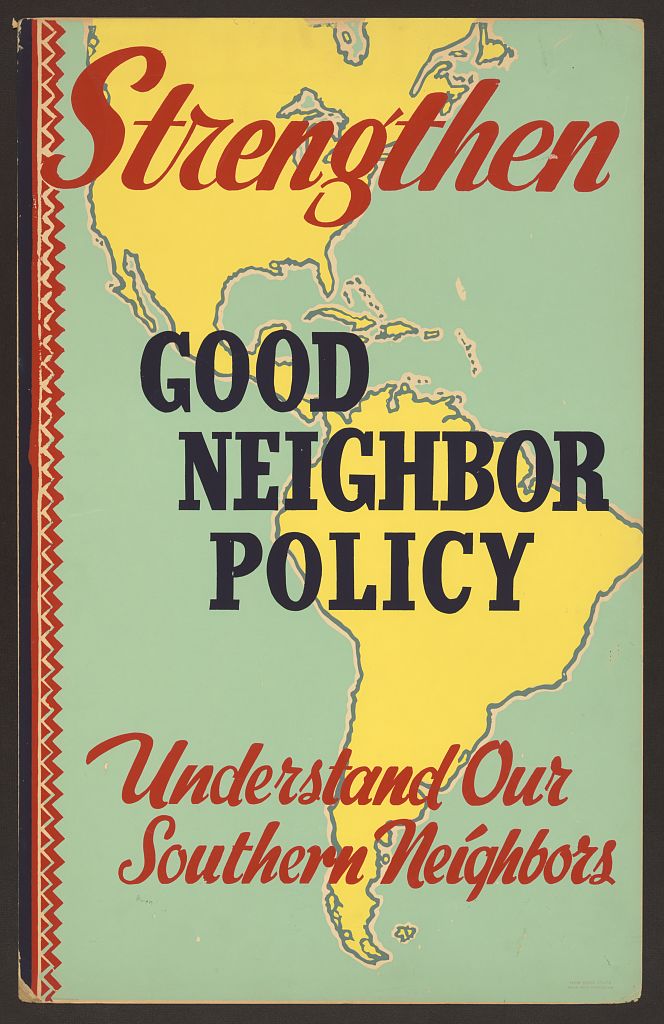

The American intrusion South began with ‘Pan-American’ promotions, an attempt to peacefully establish political and economic dominance over freshly liberated nations.. For example, in Cuba during the Spanish-American War (its war for independence from Spain), advocacy for land reforms posed a threat to the sugar industry, ushering in the sugar-invested USA’s intrusion – and victory. Consequentially, Cuba became dependent on the U.S. to pass legislation. Jose Marti, a leader for Cuban Independence, warned about this before his death in 1895. His assertion is that a successful country can only be managed by the people who live through their land’s realities, and moreover, governance requires knowledge beyond study.

“The very spirit infusing government must reflect local realities… a natural person has more to contribute to society than someone versed in artificial knowledge.”

Additionally, Marti argued that eurocentrism, the term for concentrations in European customs, has forged counterfeit authorities in the West, and U.S. Centrism will prove a peril.

“The European and Yankee books hold no answers for our problems… the scorn of our strong neighbor is the greatest present danger to Our America… it’s imperative they get to know us, or through ignorance, it might even invade us.”

While not free of U.S. influence, an example of an inward focus that shifted culture and national identity would be Mexico’s Revolution of 1910, which gave way to the Cultural Revolution in the late 1920s. After the original revolution demised over 2 million people, its following years distinguished by instability, President Calles was put into power; jumping into action, Calles initiated secularization alongside Constitutional provisions that included guarantees for workers, centralized economic control, 8 million acres of land for Indigenous villagers, and more. While the secularization incited ruthless violence and his Sonoran-born counterparts lead the country until 2000, his leadership was transformative for Mexico.

The United States’ domain in Hispanoamerica only increased, largely focused in Central America. United Fruit Company and its economically dictatorial regime, with substantial empowerment from U.S. investors, held mass amount of land around Central America, including Guatemala. There, a familiar stage was setting; a (U.S. backed) dictator had just been defeated by promises of social equality and cries to swat away foreign influence. The sentiment Marti had argued was brewing among Hispanoamerica, and Jacobo Arbenz was elected to Guatemalan office during 1950. However, the combination of his neutrality surrounding Communist conflicts and the nationalization of non-cultivated land, even with full market value repayment were ill-timed. United Fruit Company was furious, and subsequently, the U.S. began meddling. The CIA, or Central Intelligence Agency, effectively turned Guatemala into an experimentation on national security, with Guatemalan failure being the victory; “Operation Success” as it was named, led to The Coup D’etat of 1954. As we see in a piece aligning personal accounts to the series of events unfolding in Guatemala, “All over – the CIA was placing newspaper articles and propaganda films and handing out booklets that warned of the growing Communist threat in Guatemala… On [June 16th,] American mercenaries began flying bombing missions.” After the psychologically-based propaganda had been implemented, the invasion held unobstructed, and its accompanying operations were considered successful.

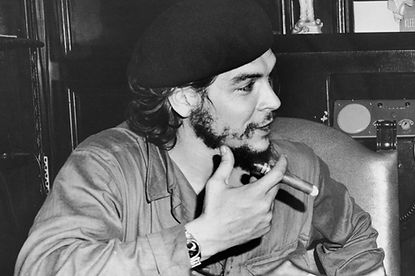

The operations in Guatemala, while temporarily ridding communist forces, spent them spiraling in the long-term; the 1954 experience in Guatemala proved a poignant knack at radicalizing former moderates, and further pervading the already extreme. In the case of Che Guevara, while already be considered “Red,” his main concerns lied with the United States’ corrupt disturbance in the country, those of which aged well. As the compilation of accounts show, his main thought of interest resembled Marti.

“Ernesto emphasized the real danger of an armed invasion organized by the United States… [and] believed it was necessary to organize an armed people’s militia, and be prepared for the worst.”

Guevara, like anybody, felt defense was justified, the uniqueness being his surety of its imminence. A connection based around June 18th, two days after the American mercenaries began bombing, Che’s story is directly connected to the invasion, “the invasion had begun, and with it, so did Che Guevara’s future.”

When looking at Hispanoamerica and Brazil in 1850-1950 from a broad perspective, it seems a conglomerate era for the region; fresh nations had to fight beyond the post-independence era to see domestically sovereign leadership, struggles for equality clashed with historic economies rooted in exploitation, countries began identifying their unique qualities of no association to Europe, and a Hispanoamerican economy proves worthy of excessive effort from the U.S. A final note, Marti’s assertion of natural governance; people would not sit easily with forced dependence, and the natural desire for reality-backed leadership would prevail.

Leave a comment