The United States’ intervention in Guatemala directly led to the Cuban Revolution, but the way in which this happened teaches an imperative lesson for modern society. By analyzing events, revolutionary leaders, and influential philosophical ideology during this time, we find something that holds relevance for all. A note for reference: it is currently October 10th, 2022 – just 4 days ago on October 7th, U.S. President Joe Biden made a statement saying “the risk of nuclear Armageddon is the highest it has been since the Cuban Missile Crisis” regarding to the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. This topic is heavily influenced by the Cold War – so even if my conclusions hold faulty, the analysis of this era is directly crucial.

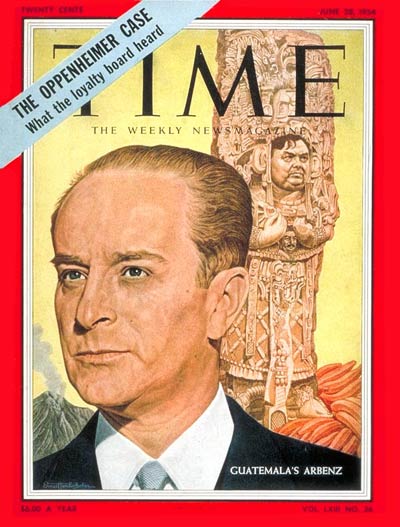

Leading up and into these revolutions, U.S. dominion spanned across all Latin America. For its own interests, the U.S. forced political and economic dependence by intentionally monopolizing the economies of various countries to its south. These monopolies were enforced by old-style oligarchic landowners who imposed dreadful labor conditions. Resistance to these oppressive regimes increasingly gained traction, but once the Cold War began in 1949, U.S. fears of Communism would have the U.S. attempting to intensify control; all leftist movements – even those similar to previous ones within the U.S. – were perceived as Soviet-influenced Communism. Guatemala, a nation that had recently concluded their second-ever successful democratic election for President, fell victim to these perceptions. President Arbenz advocated for several liberal policies, including land reform required buying back the nation’s land from United Fruit Company – an oligarchic U.S. monopoly. United Fruit Company was in bed with the Eisenhower administration.. The company was represented by the New York Lawyer and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. His brother, Allen Dulles, was director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The third brother, John Foster Dulles, owned shares in United Fruit and at one point was a member of the Board of Trustees. Therefore, in announcing his support for land reforms – Arbenz provoked the behemoth amalgamation of U.S. corporate interests, militaristic hegemony, and America’s widespread fears of communism. In consequence, the CIA turned Guatemala into a psychological, political, and combative experiment.

The goal in Guatemala was to oust Arbenz from the inside out. The CIA did this by creating connections with military officers, influential religious superiors, and other notable leaders. Through the help of their contacts, psychological warfare was implemented – designed to generate fear, anxiety, and division.

A huge part of their effort was implemented through deceptive propaganda, which was also pumped through the U.S. news cycle. Propaganda included staged recordings, disinformation broadcasts, leaflets, and more. Once the CIA felt there was enough instability, they bought Soviet-issue weapons and planted them as “proof” of the administration’s connection with the Soviet Union – permitting U.S. proxy forces to invade in the 1954 Coup D’état.

The U.S. invasion of Guatemala did not save the nation from Communistic control – the coup d’état simply guaranteed a different form of tyranny. As a country guide for Guatemala says, “For 10 years, Guatemala experimented with democracy, social reforms, and economic modernization. [The coup] brought that period to an abrupt end. [Since then,] the country has suffered the legacy of that abortion of democracy… fear, suspicion, and paranoia are almost endemic to Guatemalans… they still go about life always looking over their shoulder to see if they are being followed or watched.” This guide, which was gifted to me, contained a pamphlet for a 1994 study tour in Guatemala. In the section “A Decade of War and Repression” it says that from 1980 to 1990… 100,000 Guatemalans were killed – in the last 20 years, 38,000 “disappeared” – and less than 1% of Guatemalans who requested political asylum in the U.S. since 1980 were granted it. The CIA operations in Guatemala neglected to understand a very simple truth, one in which the U.S. was founded upon – people will become sadistic to obtain freedom.

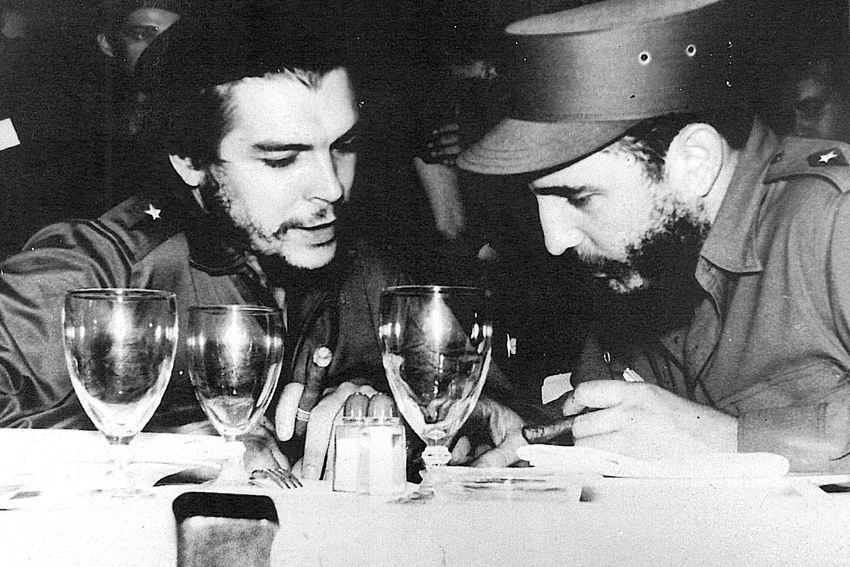

Two key leaders in the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, personally experienced the invasion of Guatemala. The duo met in Mexico following the invasion of Guatemala, and their mutual passions created a powerful friendship. Marxism gave Che and Castro inspiration for dismantling neocolonialism, and they had no problem resorting to shrewd brutality to achieve their goals. “By the end of the conflict, it was said the Sierra Maestra (a mountain range in Cuba) was scattered with the bodies of those who had betrayed the revolution.” Furthermore, in the months following Batista’s defeat, 483 of the regime’s henchmen were executed.

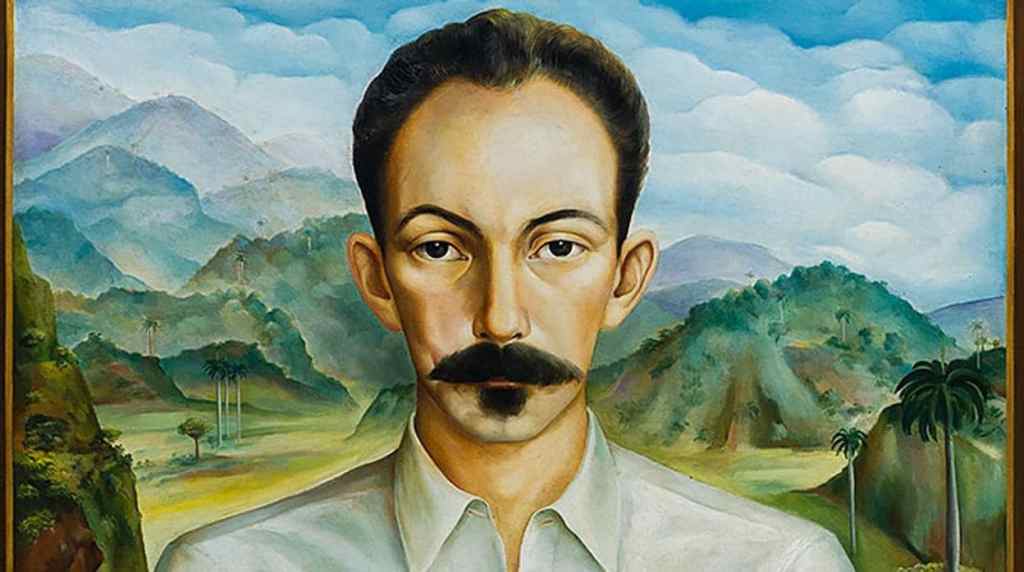

Jose Marti, a philosopher and journalist considered to be the father of Cuban Independence from Spain, wrote several times contemplating Cuba’s relationship with the United States. As a defined martyr foundation for the nation Che and Castro would eventually metamorphose, Marti’s arguments are worthy of substantial contemplation.

He asserted that any nation led by foreign or disconnected powers will inherently induce tyranny, and that without authentic governance, a nation will suffer the consequences of a society rooted in artificiality. “To know our countries and to govern them in accordance with that knowledge is the only way to liberate ourselves from tyranny.” In a different but related writing, he warns Cuba from becoming too entangled with the United States, saying “[to develop a firm footing and prosper], ideas must come from deep roots, like trees… A newborn babe is not given wisdom or maturity of age merely because one glues on its smooth face a mustache and a pair of sideburns. Monsters are created that way, not nations.” If considering Marti’s assertion in relation to the Cuban Revolution, we are able to analyze the faults of external control and what it creates. Any leadership – foreign or domestic – that is either ignorant or detached from the needs of its population will inherently impose corruption.

Assuredly, revolutionary wars against corruption are rarely peaceful – on the contrary, we can find them among the most violent, ruthless, and cold-blooded wars in history. From the Cuban Revolution, we get an example of just how far this can go. After the failed 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba had become connected to the Soviet Union, largely for defense. In 1962, a nuclear missile installation was spotted in Cuba – sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis. President John F. Kennedy basically told the Soviets to withdraw the missiles or become radioactive dust. The Soviets did agree, however, their terms included a U.S. promise not to invade Cuba. Despite petty efforts like conniving a ploy to make Castro’s beard fall out, that promise was upheld. While the U.S. had exhibited the terror of nuclear warfare during World War II, the Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrated revolution in a new age of warfare – one where risk of tyranny and foreign dominion was far more serious than a violent uprising. Instead, the threat now includes nuclear war – a form of conflict unphased by the humanistic factors found in traditional battle and wherein our historical understandings of war could be deemed irrelevant.

The Cuban Revolution is morally conflicting. On one hand, rural Cuba was finally tended to (largely thanks to the expropriation of foreign ownership), education increased, and public health advanced. On the other, liberal fundamentals such as freedom of speech and the right to travel outside of the country were not sustained.

When we look beyond the grandeur of victory, a challenge much larger than winning a war looms – upholding the ideals of which people killed and died to maintain. The ongoing struggle against oppression is a paradox. To fight a tyrannical regime, you must overpower it, but despite inspiring ideals, this is almost always accompanied by the abandonment of the values you are fighting for – the more you destroy a power you would have given your life to kill, the more similar you become to it. As an avid advocate of Jose Marti’s philosophy, Che once expressed this paradox, writing “violence is not only the monopoly of the exploiters and as such the exploited can use it too and, moreover, ought to use it when the moment arrives. Marti said, he who wages war in a country when he can avoid it is a criminal, just as he who fails to promote a war which cannot be avoided is criminal.”

When Che became the President of Cuba’s national bank – it became clear his visions were not so easily implemented. Despite his failures, he became an icon – the image of a revolutionary. By late 1964, Che became angered by increasing connections with the Soviet Union – a regime in which he saw as corruptive for Cuba. With idealistic aspirations, he decided to pursue his dream of leading a hemispheric revolution against imperialism. This dream sent him to Bolivia where his attempt to create a revolution failed – and he was captured, then executed. As a modern revolutionary icon, Che’s character illustrates the dichotomy of human nature; while researching Che, most reflections seemed to depict him with either overwhelming positivity or negativity – and I found this ludicrous. Who can lead a group of men into a bloody war with ruthless resolve and not possess – or obtain – immorality worthy of criticism? At the same time, who can expect someone who has observed mass suffering imposed by a tyrannical regime to not mercilessly fight against it?

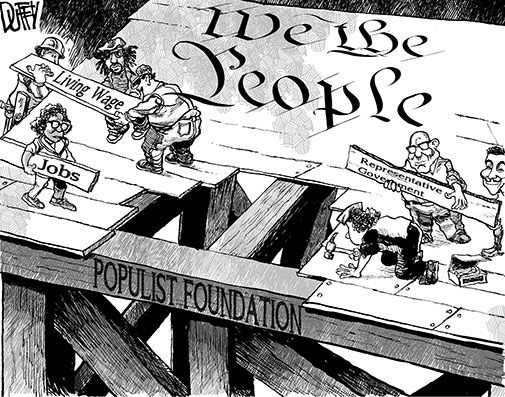

In this timeline of events, there is an overwhelming presence of ambiguity of which our modern society could benefit from analyzing. The U.S. today is plagued with division, ignorance, and corruption – all three of which link together. Currently, we see record-breaking inflation coincide with record-breaking corporate profits, a shrinking middle class, and an alarmingly growing wealth gap. With that, our political system is domineered by two parties who continue to blame each other for these increasing issues. Political discussions have turned into absolute blame, centered in “good” versus “bad” manners of thinking – and we see that polarizing narrative utilized by nearly every single one of our major leaders.

In the same argument in which Jose Marti asserts a need for authentic governance, he also discusses division. While his argument was specific to Latin America, it has shown to hold relevance to the U.S. today. “Our America struggles to save itself from the monstrous errors of the past – its haughty capital cities, the blind triumph over the disdained masses, impolitic hatred of the native races… Our genius will be in the ability to combine headband and cap, the amalgamate the cultures of the European, Indian, and Afro-American, and to ensure that all those who fought for liberty enjoy it…” And in reference to difficulties produced by foreign tyranny, “Exhausted by these problems and frustrations, by the struggles between the intellectual and the military, between reason and superstition, between the city and the countryside, and by the contentious urban politicians who abuse the natural nation… the greatest needed of Our America is to unite in spirit.”

Furthermore, elected officials using polarizing and contextually inaccurate narratives to enhance their own political interests is a form of tyranny within itself. These politicians deflect their own responsibilities using justifications far too simple to hold true weight in the intricacy of reality. As we saw in Guatemala – the instability, division, and chaos that ensued directly influenced the leaders of the Cuban Revolution. Whether instability and division be intentional or not, they have an observable connection with uprising. The U.S. has recently seen two different examples of this on “both sides.” In 2020 we saw widespread Black Lives Matter protests and riots – then on January 6th, 2021, an insurrection by devotees of former President Donald Trump. In a world so technologically advanced that conflict is inherently accompanied by unfathomable risks, it is crucial that we profoundly mature our perceptions of conflict and human nature. The problem with Che, our modern revolutionary icon, is that – like the U.S. – he professed his struggle as “the one” rooted in a moral high ground. While there is an undeniable nobility in the basis of his fight, the moment he professed the “revolutionary” as someone constructed from unwavering righteous value, he murdered his own ambitions. This idyllic fantasy, in connection to Marti’s argument, was not foraged by reality – but instead, an unrealistic yearning of which we have seen before.

As a nation founded on the ideals of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” we must recognize that simply declaring these values does not make them authentic. An effective way to prevent tyranny is to understand it within ourselves. Thus, we must form a culture that acknowledges a truth – human virtue has, and always will be, damned by human depravity. We cannot continue to blame our neighbor for our struggles, and conversely, we cannot continue to deflect the blame we hold in our our neighbor’s struggles. Through all of time, our world has been described in detail by its contradictions, paradoxes, and inconsistencies. As a society that struggles to understand and appreciate these intricacies, one question in particular forebodes: what is the consequence of a society that operates in direct conflict of the world in which it lives?

SOURCES

Barry, Tom. Guatemala: A Country Guide. 1st ed. Albuquerque, NM: The Inter-Hemispheric Education Resource Center, 1989.

Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire. 4th ed. New York City, NY: WW Norton Co, 2016.

Guatemala Study Tour: June 20-29, 1994. Red Bud, IL: La Posada Sanctuary, 1994.

Guevara, Che. “Days without Shame or Glory… A Terrible Shower of Cold Water.” Sections in Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, 128–59. New York: Grove Press, 1997.

Kronenberg, Clive W. “Manifestations of Humanism in Revolutionary Cuba: Che and the Principle of Universality.” Latin American Perspectives 36, no. 2 (March 2009): 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582×09331953…

Pickert, Reade. “US Corporate Profits Soar with Margins at Widest since 1950.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, August 25, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-25/us-corporate-profits-soar-taking-margins-to-widest-since-1950#:~:text=Across%20the%20economy%2C%20adjusted%20pretax,8.1%25%20from%20a%20year%20earlier

Pickert, Reade. “US Corporate Profits Soar with Margins at Widest since 1950.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, August 25, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-25/us-corporate-profits-soar-taking-margins-to-widest-since-1950#:~:text=Across%20the%20economy%2C%20adjusted%20pretax,8.1%25%20from%20a%20year%20earlier

Marti, Jose. “Salvation Through Originality.” Text adapted from “Nuestra America,” El Partido Liberal (Mexico City), January 30, 1891, 4.

McCormick, Gordon H. “Che Guevara: The Legacy of a Revolutionary Man.” World Policy Journal 14 (1997): 63–79. https://jstor.org/stable/40209557…

McGovern, Eileen. “José Martí and the Politics of Journalism.” Cuban Studies 25 (1995): 123–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486085….

Rakesh Kochhar and Stella Sechopoulos, “How the American Middle Class Has Changed in the Past Five Decades,” Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center, April 21, 2022),

Leave a comment