For context, I wrote this essay for a school assignment that asked me to find an inanimate object and connect it to world history. My sample is a small crystal bat – made of some unknown dark mineral. It has yellow eyes, carvings on its wings, and an x-shaped carving on its nose. I bought this little bat from the gift shop at Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, which is home to the longest cave system in the entire world. Personally, my crystal bat is a symbol of what I learned during my time exploring the cave along the “Historic Tour.”

Mammoth Cave has a rich history, especially in its relation to human impact. Many would think part of the reason the gift shop sells those bats are because you can easily find real bats in the cave, but as of recent years, they’ve become harder to find. Three of the thirteen bat species confirmed to live in Mammoth cave are listed as either threatened or endangered on the Federal Endangered Species List. In fact, I did not see a single bat during my time in the cave. The reason for this is White-nose syndrome, a fungal disease killing bats in North America. Because of this fungal disease, some bat species have seen mortality rates over 90%. In prevention of spreading it, everyone who enters the cave must clean their shoes on a biosecurity mat as they leave.[1] White-nose syndrome came to North America from Eurasia sometime around 2005, and unknowingly for a while, humans very likely contributed much to its spread across the continent.

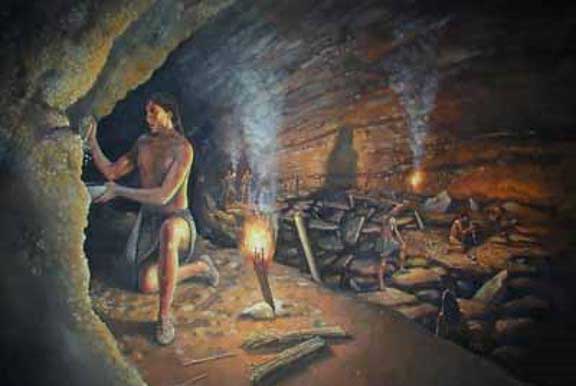

Personally, when I look at my little bat, I’m reminded of what I learned during my tour at Mammoth Cave. As mentioned earlier, this cave system has a very rich history, dating back to prehistoric times. Discoveries include human remains, reed torches, gourd bowls, woven sandals, and more. In 1935, a group of Civilian Conservation Corps workers found the remains of an ancient Native American man who got trapped under a boulder while most likely mining for the mineral gypsum.[2] Human history in the general area of Mammoth Cave goes back 12,000 years, but the actual exploration of the cave dates from 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. Prehistoric peoples extensively mined for a variety of minerals in the cave. This was a dangerous and likely scary process, as once deep enough to find the minerals, people were working in absolute and pure darkness. The only lighting a person would have had is their torch, so if it went out and couldn’t be relit, finding your way out of the cave would be incredibly difficult, if not impossible. This is how we know the resources prehistoric peoples mined for must have been very important to them, but we aren’t sure exactly why. Theories from archaeologists suggest the minerals were used for medicine, agriculture, trade, and ritual activity.[3]

As for more modern history, the cave has deep roots in African American history. In the 19th century, enslaved African Americans were forced to work in the cave and produce saltpetre, the main ingredient in the production of black gunpowder – which was in high demand due to the War of 1812.[4]The ability to produce this gunpowder came from the dirt of Mammoth Cave itself. This is thanks to the cave’s abundance of bats, who would deposit guano into the dirt, making it rich in calcium nitrate. To make saltpetre, all you’d have to do it mix that dirt with potassium. The enslaved miners built some of the first trails inside Mammoth Cave, and many of those can still be seen inside the Historic Entrance to the cave, which I had the privilege to witness.[5]

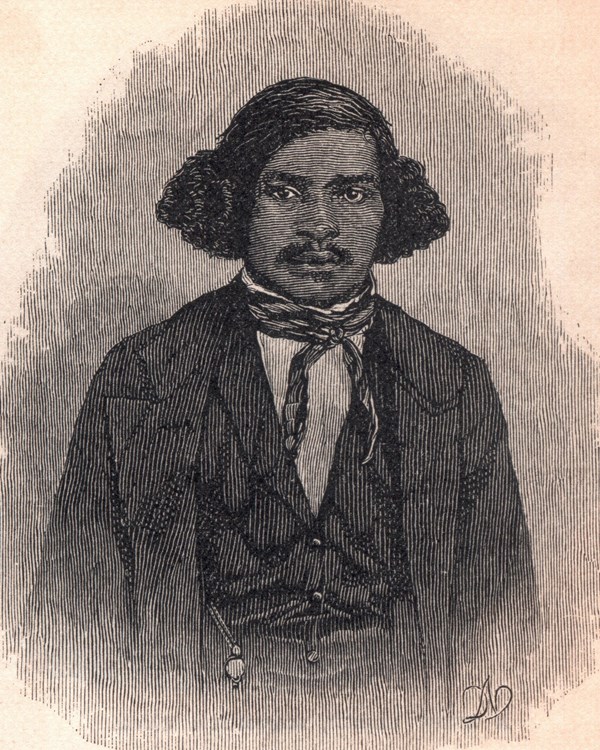

By 1838, Mammoth Cave was a popular attraction for tourists, academics, and other curious people. This is the year Stephen Bishop, an enslaved man, arrived at the cave, and would eventually be placed as a guide. However, on top of his job, Bishop joined in on the exploration of the cave. He grew to have arguably the most knowledge of the cave during his time, even drawing a map by memory of the explored passageways of the cave. He once described Mammoth Cave as “A grand, gloomy and peculiar place.” Bishop died in 1857, and remains buried at the site of the cave to this day at Old Guide’s Cemetery.[6]

During Bishop’s time, exploring the cave was not as easy of a feat as it is today, and you only got the chance to do so if you were wealthy or working within the cave. In addition, guides such as Bishop were not leading folks through a day’s long walkthrough. Instead, these were multi-week journeys over loose rocks, treacherous terrain, all with minimal lighting along the way. Since most of the people visiting during this period were privileged, they were surely dressed in fancy clothing, and while this made it much harder for women to make their way through, it didn’t stop them. Evidence is still found of broken high heels, torn clothing, and one time there was a discarded corset found at the side of a trail. In 1837, Harriet Martineau described her journey in the cave in her book Society in America; “The ladies tied handkerchiefs over their heads, and tucked up their gowns for the scramble over the loose limestone… not totally unlike the witches in Macbeth.”[7]One thing that seems not to have changed since Bishop’s days – people signing their names in areas they find to be cool or interesting. While I was exploring the cave, I found multiple carved-in signatures from people, and as the guide said, they range as far back as people have been visiting.

In the early 20th century, as businessmen and entrepreneurs realized the monetary potential of cave tourism, an era of intense competition ensued. As communities sprang up around Mammoth Cave in the mid-nineteenth century, other smaller caves were discovered. Those caves were often abundant in stalactites, stalagmites, and other fascinating formations for tourists to gawk at. However, once Stephen Bishop famously crossed the Bottomless Pit inside Mammoth Cave, expeditions into Mammoth Cave kept on pushing deeper. While landowners knew providing tours into their smaller caves would provide a good living, the real money was at Mammoth Cave. Thus, the Kentucky Cave Wars began, and developers continued looking for a any possible way to oust competition. In 1915, the developer George Morrison arrived to Mammoth Cave. Within 6 years, Morrison illegally gained access to Mammoth Cave and blasted open a backdoor he named the “New Entrance to Mammoth Cave.” Morrison quickly became the most successful cave developer in the region. With that, employees of smaller caves were directed to line the highways and draw tourists to their booths and give “official cave information” that would lure travelers to their smaller cave. The Kentucky Cave Wars also didn’t end with the creation of Mammoth Cave National Park in 1941, as they lingered until the 1960s. Despite all the damage of these conflicts, the competition encouraged people to actively explore the region for nearly a century. Those discoveries shaped the understanding of the region and determined tourist routes that are still used today.[8]

Mammoth Cave and its usage over time mimics how other caves across the world have been used throughout human history. Caves are resistant to change and keep a relatively stable climate, making them not only attractive to humans looking for some shelter, but also great at preserving any archaeological evidence.[9] The human knack of using their surroundings as a resource, whether for minerals or shelter, has been preserved by these cool labyrinths over time. In addition, I feel the history of Mammoth Cave embodies much of not just human history, but humankind itself. For example, the remains of the Native American who was most likely mining gypsum encompasses how humans are willing to undergo treacherous journeys to obtain valuable resources. During my tour of the cave, my group was told there’s even evidence of “coming of age” rituals for young men, where they’d have to wonder into the cave, perform some type of task, and return.

As ancient humans used caves for things such as home dwellings, storage, burial sites, hiding places, and religious sites – all this essentially means humans were using caves as a resource for survival or culture. As for using the dirt from Mammoth Cave to create gunpowder, this is not the only way caves have been used for war throughout history. This is especially true in modern times, as military forces would camp out in caves during both World War II and the Vietnam War.[10],[11]In regard to the tourism of Mammoth Cave, it’s interesting the lengths people would go to either for resources or simply out of pure curiosity. This is not only seen in the way women would explore for weeks on end in fluffy dresses unfit for cave exploration, but in the way ancient peoples would mine for minerals in almost complete darkness. We also see this sense of curiosity with Stephen Bishop, who single-handedly explored much of Mammoth Cave’s seemingly endless passageways.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/aa/2f/aa2fa8e4-0ef3-48d4-9415-e6f2928b1772/maca_32083.jpg)

I believe the Kentucky Cave Wars have some of the most connection to human history, as something we’ve seen for nearly all of humankind is conflict over profit-turning resources. In this regard, we can view caves as land with rich soil, able to produce healthy crops and provide for someone’s family. Just as peoples moved in and out of regions throughout history due to shifting climates, developers flocked to the Mammoth Cave region in hopes of making a decent living for their families. In Kentucky in the 1920s, caves were essentially fertile land, ready to turn over plentiful crops.

However, the absolute biggest connection I see is with regard to my little bat, and how human influence has led to a disease that’s practically wiping out bat species in Mammoth Cave. While people didn’t know they were spreading the fungus, that doesn’t change the fact human activity heavily increased the impact of White-nose Syndrome, leading to a wildlife crisis. Though now mats are used that clean your shoes, that doesn’t undo the damage that has already been done. This impact of human activity on wildlife, whether knowingly or unknowingly, is one of the biggest aspects of human history, especially in the modern day. From over-hunting bison, deforesting abundant habitats, over-farming land, burning fossils fuels, and spreading fungal disease amid exploration – humans have an immense impact from simply being human. This has not changed through all of time, though, increasing populations and advancing technology has exponentially fueled the overall impact. Questions I would ask from here: to what extent can caves impact humankind, to what extent can humankind impact cave climates/ecosystems, and how will caves continue to connect with humans in the future?

Works Cited

“African American History.” National Parks Service. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/maca/learn/historyculture/african-american-history.htm.

“Bats.” National Parks Service. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/maca/learn/nature/bats.htm.

Edward, Simon. “How Our Ancient Ancestors Used Caves.” Stump Cross Caverns – A Fun Family Day Out in Yorkshire, September 8, 2023. https://www.stumpcrosscaverns.co.uk/how-our-ancient-ancestors-used-caves.

“From Dirt to Gunpowder (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/saltpetre-mining.htm.

“Humans and Caves.” Fédération Française Tourisme Souterrain – Grottes de France, August 7, 2020. https://www.grottesdefrance.org/en/a-bit-of-history/humans-and-caves/.

Kinslow, Gina. “Mammoth Cave Scientists Studying White-Nose Syndrome.” AP News, December 8, 2018. https://apnews.com/article/7752e32dd6c04c5395bc908c4f75cf7a.

“Native Americans.” National Parks Service. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/maca/learn/historyculture/native-americans.htm.

“Prehistoric Cave Discoveries (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/prehistoric-cave-discoveries.htm.

“Stephen Bishop (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/people/stephen-bishop.htm.

“The Flame Thrower in the Pacific: Marianas to Okinawa.” Chapter 15: The flame thrower in the pacific: Marianas to Okinawa. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/chemsincmbt/ch15.htm.

“The Kentucky Cave Wars (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-kentucky-cave-wars.htm.

“Women’s History.” National Parks Service. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/maca/learn/historyculture/womens-history.htm.

Leave a comment